Potrebbe interessarti anche

What happened to the Po caviar?

Special processing of sturgeon eggs, with attention to salting, produces one of the best-known status symbols of the table, the highly prized and noble caviar. With its delicate and unmistakable taste, pure caviar is now used in kitchens all over the world but we tend to credit its spread to Eastern Europe.

Yet an almost forgotten story, which falls between popular folklore and aristocratic customs, has it that the recipe for caviar was invented in Ferrara around the second half of the 1500s by an illustrious Ferrarese, whom you may have already heard of for his fundamental contributions to the city's culinary tradition: Cristoforo da Messisbugo, a celebrated court chef for the Este family.

In the second half of the 16th century, Ferrara was at the height of its glory under the name of the Este family. Messisbugo was the pride of the ruling family, needed to astound guests with creative, scenic and innovative cuisine. The 'ante litteram chef's flair certainly did not go unnoticed, and his fame enabled him to become such an authoritative voice in his field that he required written circulation.

In his famous book 'Libro novo nel qual si insegna a far d'ogni sorte di vivanda,' published in Venice in the second half of the 1500s, the great chef describes this preparation involving fresh caviar. The recipe from Messisbugo was slowly forgotten after the fall of the Este family, but sturgeon fishing remained in vogue in the Ferrara area, and the history of caviar in the city certainly does not end there...

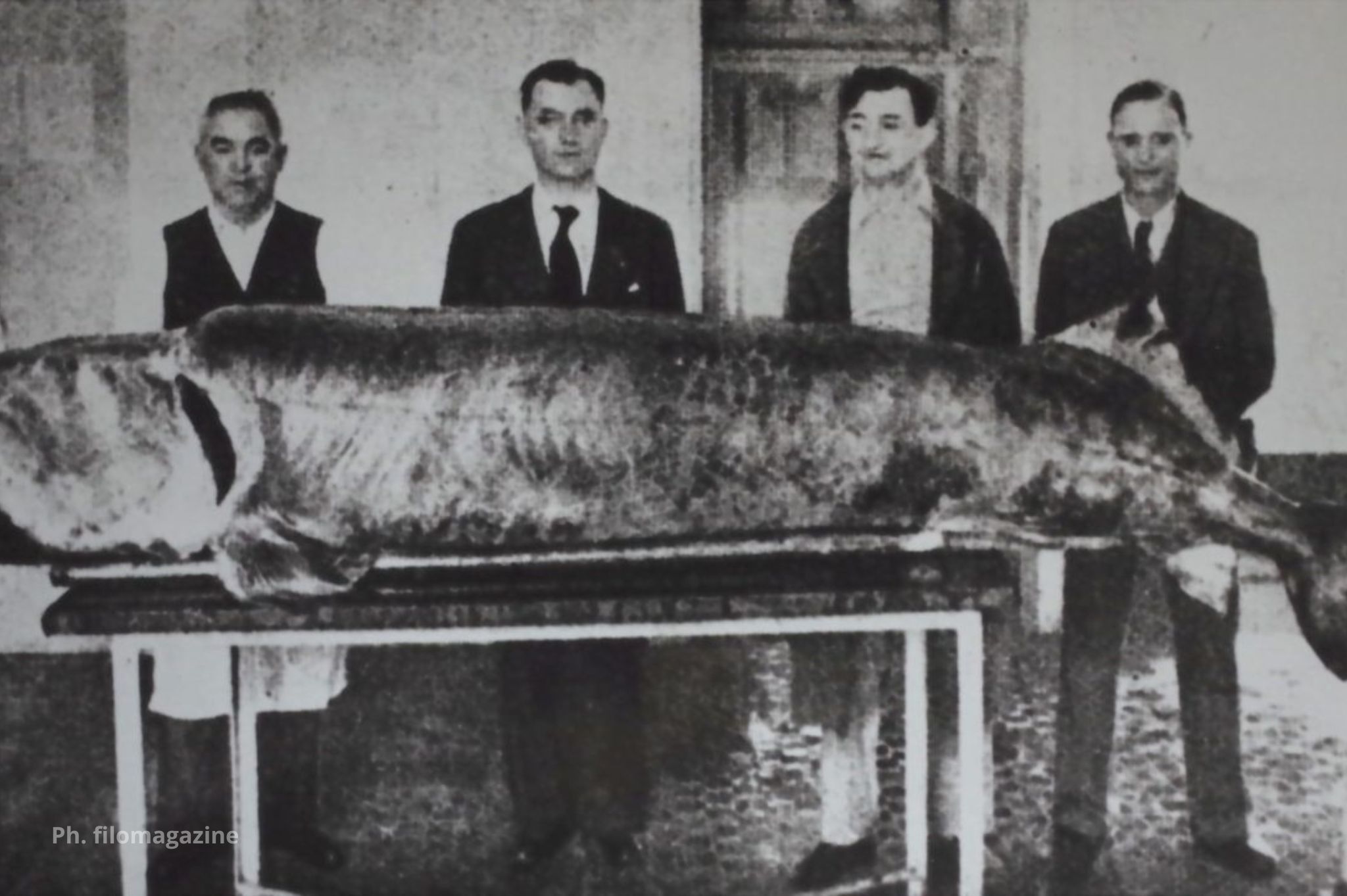

Populating the banks of Po River were many fishing communities, between Veneto and Emilia, all the way to the Delta. From mouth to mouth, stories bordering on credibility ran among the river people that featured the giants of Po, tamed by fearless men with nets and artisanal tools. Tales were told of fish that could effortlessly reach 2 meters in length by 100 kilograms in weight, but also of a few specimens of 6 meters by half a ton. A duel that the fisherman might not have been able to win.

Our story moves to Via Mazzini, in the center of the Jewish ghetto, on the corner of Via Vignatagliata and Via Vittoria. Here was located a small grocery store famous for its caviar production, the store of Benvenuta Ascoli, known as La Nuta. Nuta kept the ancient medieval recipe handed down from kitchen to kitchen until 1941, when she unfortunately died without heirs shortly after the enactment of the racial laws. The business was taken over by his apprentice, Adolfo Bianconi, who fortunately had learned the secrets of the trade. From a "store with Jewish specialties," the little store became a "deli" in 1945 and passed into the hands of Adolfo's wife, Matilde Pulga, known as Tilde. It was precisely Tilde who delivered the original recipe for Nuta's caviar, amazingly adherent to the Messisbugo original, to the Ferrara Ethnographic Center.

Unfortunately, a few years before Tilde's revelation, Sima - a company that would later be acquired by Enel - had built the Isola Serafini Dam on the Po River. It was the dam - and thus industrialization - that led to the disappearance of the renowned caviar by preventing the normal migration of sturgeons: the fish were stuck in the branch of the Po bounded by the dam, unable to make their way up the river toward the mountains to get to where the water is more oxygenated and reproduce. The small sturgeon fishing communities, isolated in the Delta, suffered a severe blow; their lifestyle, already harsh and wild, gradually became more and more miserable, and the communities slowly disappeared. The story was well described by a 1961 film by Renato Dall'Ara, Scano Boa.

Today nothing remains of the fishing communities between Stellata, Berra and Scano di Boa, and the last sturgeon was served on the table by the well-known Tassi restaurant, in Bondeno, in the 1970s. No news of the Po giant since then. Thus disappeared the legendary fish that had helped ensure the well-being of entire families of fishermen, had inspired fantastic narratives, and had sparked real 'hunting parties.' The caviar of the Po gives us an almost forgotten history capable of linking the traditions of the most extravagant medieval nobles to the humblest professions of the 1900s.

Fortunately, some recent European projects, such as the Cobice Life Project (2004) and the Cobice Sturgeon Project (2018), are working to progressively reintroduce Mediterranean sturgeon populations into the waters of the Po and its tributaries. Regarding the ill-fated Isola Serafini dam, a fish ladder was vi inaugurated in 2017 that will finally allow, after more than 60 years, the reproductive migration of fish species in the upper reaches of the river.

At the tail end of the vicissitudes of the majestic and rare fish that made Ferrara the city of caviar, there seems to be hope looking to the future: it is up to us to pass on this beautiful story to keep it alive!